These ‘vaccine passports’ are why we can have nice things

NETVIBES.COM

We’ve reached a disquieting point in the COVID-19 pandemic wherein a significant portion of the American public refuses to accept the free and wildly effective vaccines while simultaneously demanding a “return to normalcy” — and all the benefits that reopening the economy would entail. But with the Delta variant’s rapid spread threatening to send the country back into another round of social isolation, state and local governments (and numerous businesses) are seeking to strike a balance between the public’s health and the nation’s economic needs through the use of digital vaccine cards, aka “vaccine passports.” But, unlike the mRNA vaccine itself, these passports are not quite the magic bullets against COVID we had hoped.

Vaccine passports, either physical or digital records certifying that a person has been fully vaccinated against a disease, have been around since the 19th century. As early as the 1880s, students and educators in the US were required to show proof of immunization against smallpox before attending classes. In 1897 Russian scientist Waldemar Haffkine developed a vaccine against the bubonic plague. His breakthrough treatment was immediately put to use by the British colonizers of India. To help ensure that densely populated Hindu and Muslim pilgrimage sites in the country did not mutate into outbreak clusters of the disease, the local government began requiring proof of vaccination by every pilgrim before entering these sites.

With the rise of air travel in the second half of the 20th century, the United Nations adopted similar rules in 1951 and then again in 1969, dubbed the International Health Regulations. These regulations, along with widespread outbreaks of yellow fever, led to the advent of “yellow cards,” which international travellers have carried for decades to certify their immunization against a wide variety of infectious diseases.

Yellow fever is currently the only disease currently on the IHR for which countries can demand vaccination proof as a condition of entering the country, though the UN’s regulations on any disease are advisory and non-binding in nature so the responsibility for adhering to and implementing those rules falls to individual nations.

In response to the COVID pandemic, many nations already have embraced a new generation of vaccine passports. Israel has the Green Pass, Denmark has the Coronapas, the European Union (but not the UK) offers the EU Digital Covid Certificate, China rolled out its vaccine passport as a WeChat mini app in March, and Estonia uses VaccineGuard. Even private businesses are considering implementing their own systems. United, JetBlue and Lufthansa, for example, are rolling out CommonPass, a system designed to verify an international passenger’s COVID testing and vaccination status.

“This is likely to be a new normal need that we’re going to have to deal with to control and contain this pandemic,” Dr. Brad Perkins, chief medical officer at the Commons Project Foundation, the nonprofit that developed CommonPass, told The New York Times in December.

The Biden administration has made clear that it does not support the creation of a vaccine passport program at the Federal level. The President did, however, issue an executive order in January directing the State Department to work with the WHO and international aviation and travel agencies to develop standards for post-pandemic travel.

“The federal government is working on this issue of vaccine credentialing or vaccine verification or what some people call vaccine passports. So we’re going to be following carefully what the federal government comes out with,” Tomás Aragón, director of the California Department of Public Health, told the SF Chronicle in April. “If they don’t move fast enough, we will come out with technical standards of what we expect and also really focusing on making sure that that privacy is protected and that equity is protected.”

Instead, Americans are offers a hodgepodge of local and state regulations, at least those states that haven’t banned certification systems — looking at you, Arkansas, Texas, Florida, and Indiana — despite clear legal precedent affirming the government’s authority to temporarily abridge certain individual rights during a public health crisis (see: Jacobson v. Massachusetts).

Take California, for example. The Golden State recently rolled out the Digital COVID-19 Vaccine Record, a system that securely pulls the data stored in the California immunization registry. It’s the same state-collected vaccination data that is seen on the paper cards issued when you got your shots — specifically your name, date of birth, vaccination dates, and vaccine manufacturer.

“It’s not a passport. It’s not a requirement. It’s just the ability now to have an electronic version of that paper version,” California Governor Gavin Newsom explained during a press conference announcing the system’s rollout in June.

The system can also store a scannable QR code on your mobile device so that businesses and venues that do require certification of full vaccination prior to entry can do so easily. The QR code is built on the non-profit SMART Health Card technology, which means that only SMART-compatible scanners can actually read the codes. And in San Francisco, that’s literally all of them. This is a built-in security feature ensuring that some random clown at the bar can’t surreptitiously scan your code using the generic QR reader on their phone and get access to your information.

However, the system’s rollout has not been without its hiccups. This reporter specifically has spent the past six weeks attempting to resolve an issue with incomplete vaccination data being reported to the registry. (Basically, it reads that my second dose is the only dose I received.) The CDPH declined to comment on how many Californians have registered for the service and how many of those registrants have run into similar problems, though the agency has set up a virtual agent to help guide users through the process of alerting the state to any mistakes or omissions.

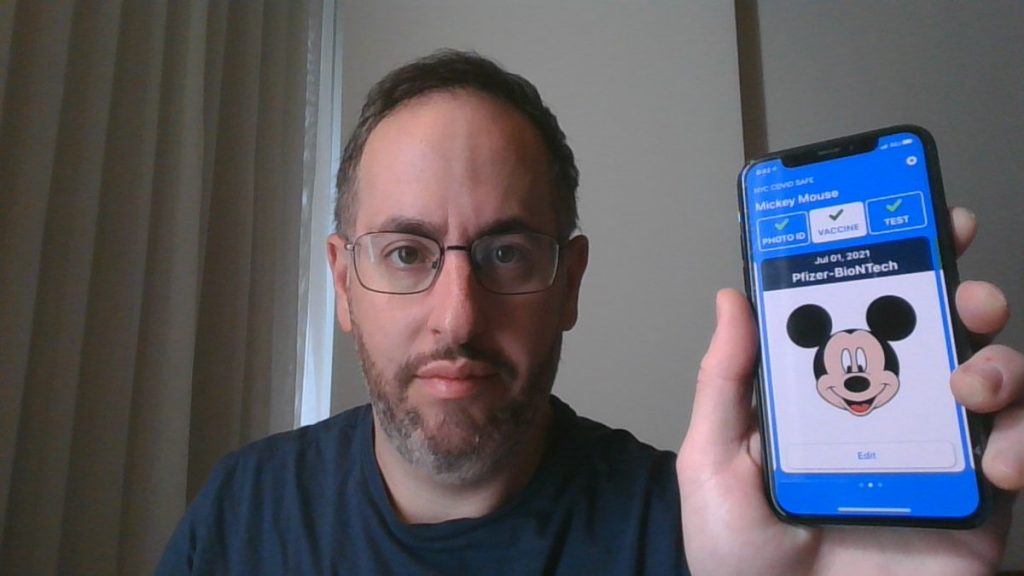

New York, on the other hand, has not one but two competing vaccine verification systems, neither of which has proven particularly reliable, trustworthy or useful. At the state level, you’ve got the Excelsior Pass, which operates in a similar fashion to California’s DCVR system — pulling immunization data directly from the state’s registry — and leverages IBM’s proprietary blockchain technology to maintain data security and user privacy. At the local level, New York City has rolled out a passport app of its own, dubbed the NYC COVID Safe App, which for all intents and purposes is a half-assed image storage app that is ridiculously easy to spoof.

As you can see from the above tweet, STOP founder and NYC-based privacy advocate Albert Fox Cahn was able to get the NYC app to accept a picture of the iconic rodent in lieu of his actual state-issued vaccination card.

“I uploaded a photo of Mickey Mouse when I registered for it and then it gave me a pop up box saying are you affirming this is accurate,” Cahn told WNYC earlier this month. “You click yes. And then you’re done.”

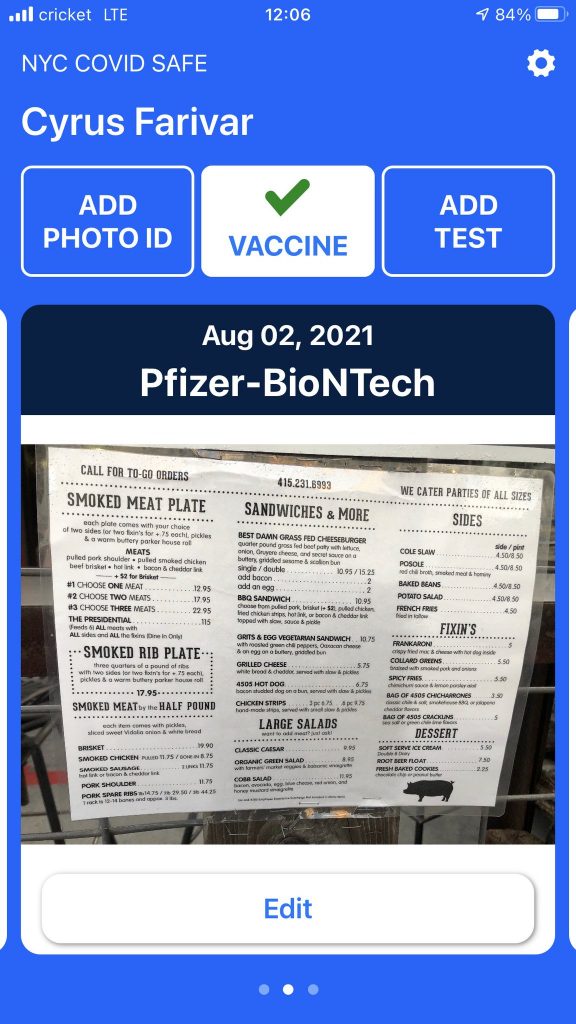

This feat was easily replicated by other users, including San Francisco-based journalist Cyrus Farivar, who used the menu from a local BBQ joint as his photo.

As you can see from the above tweet, STOP founder and NYC-based privacy advocate Albert Fox Cahn was able to get the NYC app to accept a picture of the iconic rodent in lieu of his actual state-issued vaccination card.

“I uploaded a photo of Mickey Mouse when I registered for it and then it gave me a pop up box saying are you affirming this is accurate,” Cahn told WNYC earlier this month. “You click yes. And then you’re done.”

This feat was easily replicated by other users, including San Francisco-based journalist Cyrus Farivar, who used the menu from a local BBQ joint as his photo.

“The NYC COVID Safe App was designed with privacy at the top of mind, and allows someone to digitally store their CDC card and identification,” Laura Feyer, spokesperson for Mayor Bill de Blasio, told Gothamist in response to these reports. “Someone checking vaccination cards at the door to a restaurant or venue would see that those examples are not proper vaccine cards and act accordingly.”

“The functionality of this app really raises the question, why did the city create it to begin with, because like so many other vaccinated New Yorkers, I had a photo album with my vaccine card months ago,” Cahn told Engadget. “It’s unclear how this was anything more than a publicity stunt to roll it out as a new city app.”

“And then on top of that, to then make these broad sweeping statements that how the app is unhackable and to also say that there’s no privacy impact when the app is also collecting your IP address and record of every time it’s open,” he continued. “It’s not a huge amount of IP information but it’s information that the city was never collecting before, it’s information that they simply don’t need.”

What’s more, the NYC COVID Safe app’s lackisadical security also makes it prone to exploitation by anti-vaxxers, like noted area conspiracy theorist, Joe Rogan. Since the app doesn’t independently verify any of the information it is displaying, instead relying on bar, venue and restaurant staffers to make the determination as to whether a photo is legitimate or not, malicious users could easily upload a photo of any vaccine card — whether it’s been photoshopped, acquired from a friend or bought on on the black market (for $400).

The state-run Excelsior Pass has run into privacy issues of its own. For one, its reliance on IBM’s blackbox blockchain system provides virtually no accountability or transparency in how the system actually operates.

The “thing is highly engineered, it has all these layers of registration, verification, and a customized QR code,” Cahn said. “That’s raising far more important privacy issues because the state is quite clear that it doesn’t use location services. But since each scanner is registered to a specific business address, every time you scan that QR code, the state and IBM are collecting a record of where you were and when, and we haven’t done any clear information on how long that data is retained.”

What’s more, an experiment conducted in April by Cahn found that even with the blockchain assurances, the app was remarkably easy to hack. “After getting consent from an Excelsior Pass user, I tried to download their pass, logging into their account using nothing more than public information from social media. Eleven minutes after he gave me the greenlight, I had a copy of his blue Excelsior Pass in hand, valid for use until September,” Cahn wrote for the Daily Beast.

“This city app really just speaks to the dysfunction. Here in New York, the rivalry between the city and state, the fact that we have a mayor and the governor who can’t stand each other, and it is not addressing a technical need,” he lamented. “These apps are such a debacle that we just need to go back to old-fashioned paper records.”